When we were little kids, baby groms tossing our boards into windward beach breaks and splashing into the waves, we’d all heard about the Aikau brothers.

They represented the best of what we were.

They were the premier big wave surfers in this pastime invented by Hawaiians that was fast becoming big-money sport. They were brave, powerful, at one with the water and the world.

We’d heard about them before we ever saw the pictures. When we saw the pictures, they were beyond belief.

They were tiny shadows on walls of water, thousands of gallons of blue roaring overhead, hungry to swallow them, their arms stretched like mighty frigates, aloft over boards pointing toward freedom.

That was who Eddie Aikau and Clyde Aikau were to us. They were mythical. We ripped their pictures out of the surf magazines and tacked them on our walls right next to Bruce Lee.

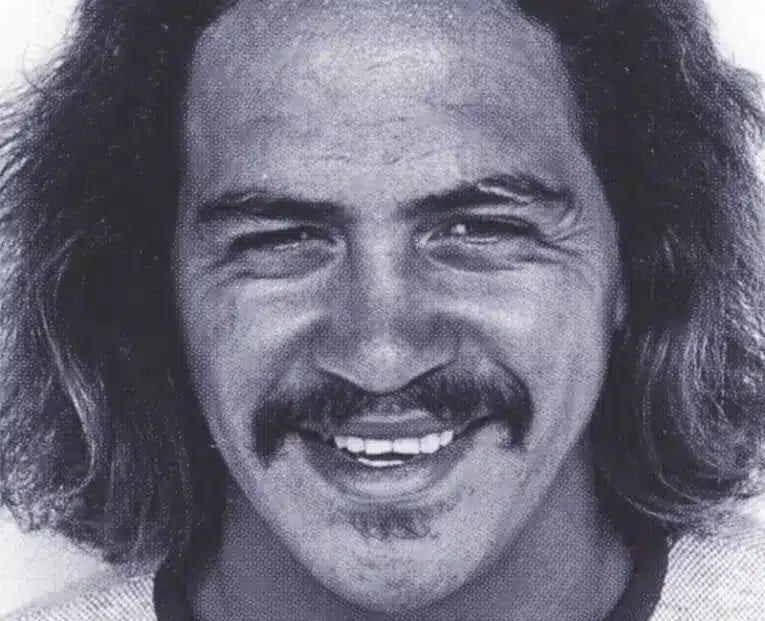

I can still see one of those photos of Clyde now, all mustache and windswept hair bleached by sun and salt, laughing like, YEAH BRAH. Me, I do this everyday.

Clyde passed away on Saturday night. In recent years he had been battling heart problems and pancreatic cancer. His death followed that of his jovial older brother, Solomon III, two years ago. His gracious sister, Myra, who over the years has led much of the family’s activities behind the scenes while Clyde has served as their public face, is the last survivor of her generation.

Born in Kahului in 1949, the youngest of six children to Solomon, Jr. and Henrietta Kahaunani Aikau, Clyde Aikau’s destiny was most intertwined with his older brother and closest friend, Eddie, who was three years his senior.

“Eddie was the leader of everything,” Clyde once told me. “He always seemed to get a heads up on something before we even knew.”

At ten years old, Clyde followed Eddie into the surf at Walls in Waikīkī, and they were soon bodyboarding there every week on their own homemade paipo boards. By the mid-60s, they were piling into the family’s grey-paneled truck to make the drive to the North Shore so they could paddle out at Haleiwa, Chun’s Reef, and Laniakea.

It was not long until Waimea Bay, where Hawaiians had surfed for centuries, finally called.

On November 19, 1967, Eddie made his debut in the big waves at Waimea. The camera men in helicopters and the magazine photographers on the beach and the cliffs caught a young Hawaiian man in red and white board shorts on a red quiver, surefooted and bold, who looked like he had been surfing it for years.

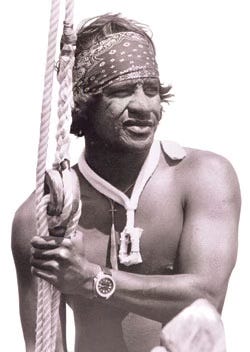

Two years later, Clyde followed his older brother into the winter surf at Waimea and similarly distinguished himself as a charger. The magazines filled with pictures of his exploits.

A decade later, the two brothers were at the top of their sport. But Eddie had begun pulling away from the professional surfing world. He was devoting himself to preparing for the second voyage of Hokule’a, as part of a Native Hawaiian project to rebuild and sail a canoe that would retrace the path from Hawai’i to Tahiti.

The voyage of this wa’a would reconnect and recover cultural and navigational knowledges that had connected Polynesians for centuries, bury the racist theories that they had simply drifted across the Pacific, and revitalize Native people.

Then on March 16, tragedy struck. The Hokule’a, with Eddie aboard, set off from O’ahu and immediately encountered a major storm. Somewhere between O’ahu and Lana’i, the ship capsized. In a desperate bid to save the crew, Eddie set off on his surfboard through raging seas to paddle the several miles to Lana’i to get help. He never returned.

To this day, three words most surfing fans know are: Eddie Would Go. The words decorate branded T-shirts, caps, and bumper stickers. They resound every time the big wave contest now named after him — “the Eddie” — goes off at Waimea Bay.

Clyde told me, “Anybody who rides big waves knows that fear is always a factor. That's reality. But there's a rule that that if you're not in one hundred one percent, you shouldn't be riding.”

It turns out this was only the beginning of the Aikau ‘ohana philosophy.

By the end of 1969 both of the young Aikaus had been tapped to serve as lifeguards at Waimea Bay, plucking countless hundreds of people — soldiers on leave from Vietnam, tourists, locals, even some of their most experienced surfer friends — from its treacherous winter waters.

Looking back on those days, Clyde told me, “The golden rule is, get to the victim. And the second golden rule is: no matter how giant the wave is, no matter how you get beat up, no matter how hard you get held down, you're not going to let go of the victim. Because once you let go, you lose them, man.”

Anyone blessed to have known the Aikau family personally — and in the islands, that seems like maybe most people — knows that Eddie Would Go wasn’t about merch or even just tackling big waves, it was about more: a love for the people, the lahui. Commitment, even to the point of sacrifice, would be the highest demonstration of this aloha.

The Aikaus had come to O’ahu in 1959 from a modest plantation camp in Kahului, Maui. After they moved to Honolulu, their father found work caretaking the Yee King Tong Chinese cemetery in Pauoa, nestled in a gully above downtown Honolulu at the beginning of Nu’uanu Valley.

Pops Aikau enlisted the entire family in this task, and the local Chinese hui that had set up the cemetery soon entrusted the land just downhill from their small ceremonial building dubbed “the bonehouse” to the Aikaus to build their home. In that ineffable Hawaiian way, it all seemed meant to be, a poetic return. To this day, the ‘ohana resides there and looks after the graveyard.

The land abuts one of Queen Liliu’okalani’s personal gardens, Uluhaimalama. In 1893, American colonists imprisoned her in her own palace and forbade her to communicate with her people. So her supporters instead sent her messages by wrapping flowers from the garden in Hawaiian-language newspapers.

Generations later, the ‘āina, the wai, and the kai – the land and the water - were still sending messages. When the Aikau brothers finally made it to Waimea Valley and its bowl-shaped bay, which forms a natural arena for big-wave surfing, it was like coming home for them. In kahiko times their ancestor Hewahewa, a trusted kahu of Kamehameha I, had the responsibility of caring for the people, land, and the bay of this wahi pana. When Eddie and Clyde began lifeguarding at Waimea Bay in their early 20s, the kupuna must have looked down and smiled.

Much has been made in surfing histories of the Californian haole transplants who made Waimea Bay so famous that it would be name checked (and badly mispronounced) in the Beach Boys’ “Surfing U.S.A.” When the young Aikaus came to the Bay, they had only one person in mind as inspiration. “Bottom line for Eddie,” Clyde recalled, “was he wanted to ride Waimea Bay because of his hero, Kealoha Kaio.”

Eddie and Clyde’s next biggest desire was to win the biggest professional contest in the world at the time, which was named for their hero, Duke Kahanamoku. But in the first Duke contest, held in 1965 at Sunset Beach, Native Hawaiian surfers were excluded from the list of invitees. Eddie and Ben Aipa launched a protest by paddling out just before the contest horn sounded, tearing up the waves in a freestyle session just to remind the organizers that they belonged there. The following year, they were included.

In 1973, the contest moved from Sunset to Waimea for the first time and Clyde - who had been listed that year as the first alternate and entered only after another contestant had dropped out - beat his older brother to become the first kanaka maoli to win the contest.

Everything seemed to be going well in the Aikau ‘ohana. Clyde was graduating from the University of Hawai’i at Mānoa with a degree in sociology, the first in his family to secure a college degree. Just two weeks after his historic victory, Clyde was celebrating with hundreds of his friends and family members. But after the family caravaned home to the cemetery from his party, his brother Gerald — who had gone in a VW Bug with a different friend — died in a car crash on a lonely bend of a country road.

Gerald’s death plunged the family into the depths of despair. Eddie’s tortuous healing journey eventually led him to join the Hokule’a voyage. “Prior to the Hokule’a, us Hawaiians kind of was a low key, kind of like, ‘Maybe I kind of wish I was born haole.’ Maybe I would have had more this or that,” Clyde told me. “But the Hokule’a really ignited the pride of Hawaiian people and especially Eddie.”

Yet after Eddie disappeared, Clyde’s own personal crisis deepened.

He headed out on tour to surf around the world, but his heart was no longer in it. When he came back, he moved back to the graveyard where all of the Aikau children had returned to be near their mourning parents. Clyde would not return to Waimea Bay or the North Shore for another six years.

Clyde had always been the hustler of the family.

As a kid he called out to passersby at the Maui County Fair offering to shine their shoes. In Honolulu he went to Aloha Tower when the cruise ships docked to dive for coins that tourists tossed from the deck. On corners in Waikīkī, he sold coconut frond hats he had made.

Before long Clyde had set up a beachboy business at Kūhiō Beach teaching tourists to surf and canoe paddle. And, ever in service to the community, he also began working for the Department of Education to provide special services and programs for unsheltered children and families.

In 1986, he felt called to return to Waimea Bay in the first big wave contest named for his brother.

By then he was 37, and a new generation of big-wave surfers from California was taking over. Clyde decided to compete, paddling out into the lineup on Eddie’s pintail board that he had found forgotten under the house. After a grueling competition in raging surf, Clyde found himself in the finals.

As he was paddling out for the final heat, he spotted two turtles poking their heads out of the water at him. “They stuck their head out of the water and looked at me,” Clyde recalled, “and was kind of saying, ‘Follow me, follow me.’”

The honu led him through the churning whitewater beyond the lighthouse and even further past the mouth of the bay, until he was a hundred feet past the other surfers. He was sitting in the deep blue far ahead of the lineup in a kind of no man’s land, or so it appeared to the others.

Suddenly the biggest swell of the day reared up before him, sixty feet high, and as the surfers behind him scrambled to climb over it, Clyde pivoted and took off, working the wave all the way to the inside break as the crowd on the beach erupted in cheers.

When he turned to paddle back out, the honu suddenly reappeared. He followed them back again to the outside of the Bay to catch another monster wave in.

That was the way he won the first Eddie Aikau Classic — with the help of two spirits, his ‘aumākua.

One time Clyde told me, “Don't forget this one about this family: we're very spiritual.”

Then he began telling me stories about mystical things he said had happened to his family, involving births, deaths, music, and menehune. He capped it with the most breathtaking story of all.

In 1995, Nainoa Thompson, who had been the navigator on the fatal journey in which Eddie disappeared, invited Clyde to sail on the Hokule’a from Nuku Hiva in the Marquesas Islands back to Hawai’i. He was trying to recreate a 16th century voyage that had brought islanders from across Polynesia together. Clyde immediately accepted.

The night they prepared to leave, the crew slept in a remote village near the ocean that could only be accessed by hiking down a steep cliff.

“The last night us guys was there, I was sleeping in this ten-by-ten room with one of my crew members on the other side of the room,” Clyde recalled. “Three times that night, my crewmember woke up, and she look over to my side of the bed. She sees somebody sitting down in a chair, looking over me with a headband on.”

The day Eddie had left O’ahu in 1978, pictures had shown him wearing a bandana he had pulled over his hair.

Who else could have visited him in Nuku Hiva?

It’s 2021 and we’re out at Kūhiō Beach where Clyde is at his beachboy stand, a little umbrella in the sand surrounded by surfboards, slippers, and a canoe.

Clyde is in his seventies. He’s retired from big-wave surfing, but he’s still a ball of energy, hard for folks to track down. Maybe he’s helping his wife run her dog-care business, or maybe he’s clearing tall grass on his land, or maybe he’s at his DOE job visiting homeless kids. He will do this until his body will no longer let him.

Today is not a day for tourists. The summer swell is delivering set waves over the reef that are breaking well above 6-feet Hawaiian, meaning double overhead. Even on the inside, the ocean is rough. One canoe full of tourists tries to get through an inside wave but the paddlers are too sluggish and a wave flips the canoe over. For a moment, the roiling water is full of panicking tourists.

“Hoooooo!” Clyde cries, leaps up, grabs his safety floater, and runs toward the water.

Seeing Clyde, the rest of the lifeguards and watermen hasten to his rear. Fortunately the crisis is averted as the canoe men deftly retrieve the tourists and flip the canoe back over. They turn the wa’a around and take the rattled visitors back towards the shore. Clyde and the watermen retreat back to the beach.

As I remember that moment now, it makes me think of the kupuna he was: no matter his age, Clyde would still go.

A few days later I am sitting with Clyde on his rusty utility truck in the corner of his Waimānalo land, listening to the birds singing and him talking story under the shade of an old mango tree.

The great producer Nina Yang Bongiovi had introduced me to Clyde, Myra, and Solomon so that I might draft a screenplay on Eddie. You always go into these things hoping to get The Story. But here is Clyde, giving me something even bigger.

“You want to be a serious big wave rider, you can't be riding for fame, glory or money,” he is saying. “If you're trying to trying to make money, well, it's a long shot. And the risk, I think, is not worth it.

“I tell all the big wave riders that you're going to eventually get into a situation where you're right at the edge of time and the only way you're going to pull yourself out is not all the money you made. Or it's not all the front covers that you made. The only way you're going to survive is to dig deep in your inner self to survive.

“I mean, how do you think these guys ride these mountains, especially with no rope? There's something way beyond the physical attribute of what they have. It's something that they dig deep within their soul and know that they're at a place that they want to be.”

Clyde had competed in every Eddie contest that ran at Waimea Bay until the age of 66, when he told his relieved family and friends the next would be his last.

Privately he had been keeping up a seven-month training regimen, tracking his diet, his conditioning, his breathing. When swells hit the eastside, he left his Waimānalo home early in the morning to paddle out four miles to Mānana/Rabbit Island and surf the rare wrap-around break alone.

In 2016, the storms barrelling down from Alaska to the North Shore were hitting especially hard. The Eddie contest does not go every year. It only runs within a three-month window when waves consistently hit 40-feet Hawaiian — that is, 80-foot faces. Clyde had surfed two early big swells in the Bay and felt confident that when they called the contest, he would be ready.

When the biggest swell of the year did hit, the water was coming up all the way up the beach nearly to the parking lot – the highest Clyde had remembered since 1969. Under certain conditions, Waimea thunders so hard it simply closes out.

That night, Clyde said, “It's not closing out three times in one day or four times in one day, it's closing out every 15 minutes.”

He thought to himself, Oh shit! I trained on big, but maybe not this big!

Before dawn, lifeguards and contestants passionately debated whether the surf was too dangerous for the contest. By daylight thousands of people had already gathered along the beach and cliffs to bear witness.

Clyde stepped in and, because he was an Aikau, his opinion held greater sway. “If you don't want to ride today, it's OK. There's always another day. Tell you the truth, I can't blame you if you don't ride today. I mean, it is fucking gnarly out there, man,” he said.

Then he turned to the lifeguards and told them what conditions to prepare for. The contest was going to go.

He was scheduled for the third heat against the local North Shore-bred prodigy John John Florence, more than forty years his junior. “I got my pit crew getting me ready, psyched up, everything. My body leash, my vest, my cannisters, everything. So I'm pretty calm,” he recalled.

“I had a plan the whole time, and the plan was this: first big set comes in, no matter who's on the side of me, I'm going. I don't care where they are, what they're doing, they're on the inside of me, they're on the outside of me, they're in front of me. Uncle Clyde is coming, boom!”

“The wave come, brah. Me and John John paddling out. Boom! I turn around and I start paddling, man. I stand up. Coming down.

“My whole fin is ten feet in the air. I hit one bump in the first five feet. And I'm dropping down this fucking 80-foot wave, brah.

“I hit my second bump and I go airborne again and I lose it, brah. I fall on my right shoulder. And I'm in the wipeout. I pull my cannisters, I come up. Lifeguards come get me, put me in the channel.

“My arm just doesn't feel right. But I get myself together again and I go back out. I was literally surfing with one hand the whole day.

“That first round I come in, paddling with one hand, I get caught by the shore break. It's throwing me into the rocks. When I come in, all the lifeguards came help me come in, they take me straight to the tent with the doctors.

“My arm can't move. All I told the doctor was get my shoulder enough so I can go out one more time, you know? Because I wanted to finish it.

“Everybody screaming, ‘Uncle Clyde, Uncle Clyde, Uncle Clyde!’ So I hit the water paddling out with one hand out in the middle of the bay.

“Brah, the biggest set of the day. It's 80 to 100 feet. Closing out. One wave from Sunset to Haleiwa. There's no horizon, brah, It's just one giant wave coming through.

“Me, I knew that I was done because, I mean, I can't go anywhere. But so, actually I’m taking my time now and I'm kind of hyper breathing. Hyper breathing, hyper breathing, hyper breathing. Finally, man, the wave is right in front of me standing up. I let go of my board. I go down. I go down, I go down.

“The wave breaks. It grabs me, shoves me into the sand on the bottom. And I'm trying to come up and I can't. I can't.

“I'm going, ‘Oh shit! Wow.’ I mean I'm not panicking or nothing. I'm just going, ‘Oh shit, Wow! ‘

“Finally I pull all my cords. I pull all my cannisters. I pop them and my vest inflates and then I start coming up. But I still gotta fight coming up. I'm fighting. It's been already a couple minutes gone. Going on three minutes. Fighting, coming up fighting, brah. Fighting.

“I get to from here to the top of that tree,” he says, pointing fifteen feet up to the top of the mango tree.

“I'm gone. I'm gone, brah.

“Next thing I know, I'm looking at the entire bay and it's white.

“Mountains are white. The whole bay is white, and it's quiet. I feel like I'm in church. It’s quiet. I'm not panicked. I'm very calm, very calm. So I'm looking around, nobody around. And it's just all white, brah.

“All of a sudden, I wake up and I'm on the top of the surface and I'm floating. And then everything comes back blue.”

He lived to be 75.

I can see Clyde plucking his guitar kī hō’alu style on the steps of the bone house at the graveyard, singing “Pauoa Liko Ka Lehua” in a surprisingly gentle lilt.

The mele is a sensual tribute to a ravishing young dancer. The lyrics trace the cut and wave of her dress as she sways, exciting his “endless desire.” It is also a song of place, a mele wahi pana that evokes the rush of water down the ‘Auwaiolimu stream from the Ko’olau cliffs down through Papakolea and out along the northern edge of the Aikau’s cemetery toward the ocean.

When Clyde is signing in the graveyard, the ghosts gather. They dance to celebrate the unity of two lovers in the night, the unity of the land and the water, the unity of the living and the dead.

E ola. E ola.

Somewhere in heaven, which I am certain looks like Waimea Bay, Clyde is up there and he’s laughing again with Eddie and Gerald and Solomon.

Jeff, reading this felt like it was pouring out of your heart and transporting me to your homeland. Thank you for sharing these stories! I just read about Nainoa Thompson in James Doty's, "Mind Magic." So cool to get a bigger version of that story.

Loved this! As someone completely outside of this world, thanks for bringing me into it for these moments. What a life, what a tribute.